From left to right, the four walking are: Ralph Grooms, top turret gunner;

Art Starratt, bombardier; Walter LeClerc, pilot; and a German soldier

(Above photo from the Starratt Family archives)

The crew or what was left of it: LeClerc, Ellis, Killduff, Grooms, and Art, were marched out of the field to a nearby cafe.

Cafe Rusthoek

(Courtesy of the Family Photo Collection

of Mr. Cor Verschoor, The Netherlands)

Each man was interrogated as they all sat around a table. Each would give only their name, rank, and serial number, each except the Co-pilot, Jim Ellis, who argued with the Germans, taking them to task for asking anything beyond what was required by the Geneva Convention. Jim continued in this fashion which only resulted in him spending extra time in interrogation. The Germans who had first come to the plane, were soon replaced with Gestapo. It was getting dark. All five men were placed in a closed van, in complete darkness, and were driven to their next destination.

They all assumed they were going to be shot.

Instead, they were then taken to a jail in Amsterdam. All but Jim Ellis. It would be another day or two before the Germans were through with him. The jail had underground cells covered with green mold. It was dank, and there were no windows. The guard escorted Art to his cell, opened the door, and said, "For you, ze Roosevelt Suite." The "Roosevelt Suite" was a very small cell with an iron cot. They were there for another 3 or 4 days of interrogation.

Eventually Jim Ellis showed up. The rest of the crew were taken to the railroad station where they boarded a passenger train bound for Dulag Luft in Oberursel, the main German interrogation center. Jim, not giving the Germans an inch of slack, would be left behind again.

There were some Hitler Youth on board the train who immediately started harassing the crew. One of them came up to Art, and with his face in Art's said, "We bombed New York last night!" The teenager seemed like potential trouble, so Art simply said, "Oh really? Hmm."

They were soon transferred to a boxcar of a freight train. There were roughly fifty prisoners in one end of the car and four German guards at the other end. Some of the prisoners had been in captivity for quite some time, and were not well. There was not enough room to sleep. Art remembered that if you stretched your legs out, someone would put their legs on top of yours. Then someone else would put their legs on top of theirs, and so on. As the legs stacked up like cordwood, the man on bottom would pull his legs out, and place them on the top of the stack. And so it went.

The train would wait for long periods on sidings as higher priority trains would pass. When the train finally arrived in Frankfurt, the German guards formed a circle around the prisoners to move them through the train station. The German civilians were angry and crowded around the Group. The guards had sub machine guns and aimed them at the crowd. To their credit, they were not going to let things get out of hand.

At Dulag Luft, the main German interrogation center, Art, like many before him, was amazed at the information the Germans had compiled on him. The Germans had his engagement newspaper clippings, his graduation pictures as a 2nd lieutenant, his home address, and much more.

Although Art had been briefed on what to expect if he found himself at Dulag Luft, it was unsettling. He knew not to discuss anything with other prisoners as well, since the Germans were known to slip impersonators in with the prisoners. The interrogator told him that they knew that their commanding officer had not flown with them today due to a head cold. Art was stunned. This information was true. Could someone on the base at Polebrook be giving them information? At one point, the interrogator said, "You think we don't know about your secret bombsight?" Then he took Art into a room containing a complete Norden bombsight.

When the Germans were through with the prisoners at Dulag Luft, they were again loaded into boxcars for the trip to the prison camp. Art knew he'd been listed as missing in action on the day he was shot down, and he now wanted to get word out that he was still alive. At the station, the prisoners were sometimes given a chance to send a cable home. Art sent a cable to his Dad simply saying that he was okay, and was being treated well. He knew this type of cable might actually be sent.

Art, George Killduff, and Walter LeClerc were loaded onto a train headed for Stalag Luft 1. Jim Ellis would be sent along later. When the train arrived at Barth, the prisoners were unloaded, and marched through town towards the camp. Some of the citizens threw rocks at the arriving POWs.

Upon hearing that his son was listed as MIA, the "missing in action" verses were added to a poem that had been written in tribute to Art by his father. The entire poem is as follows:

THE BOMBARDIERS

By Simon P. Starratt

Bombardiers - what do they do?

Men with hearts - and courage, too?

Gentle, kind and loving hearts.

Educated in all the arts.

Men from every walk of life

Joined together to end all strife.

God fearing men in the stratosphere

With oxygen masks, and eyes that are clear.

They look through the bombsight - what do they see?

A city in darkness - or a ship at sea.

Not out of hatred do these men fight

But for love of freedom and all that is right.

And when they signal "Bombs away" -

It means death and destruction every day.

To those who would destroy our way of life.

That's why these men are in the strife.

With nerves of iron and hearts of steal

They make the Nazi's rock and reel,

"Til every city, hamlet and town"

In Nazi Germany is mowed down.

On to Japan - the watch word will be

To blast that island out of the sea.

All hail the rest of the men who fly

But the Bombardier must have the eye

To hit the target day or night

And help the rest of the boys who fight.

And when the enemy is crushed and it's clear -

We'll take our hats off to the BOMBARDIER!

"Missing in action", the telegram said.

Missing in action, I know he's not dead;

For God in his mercy has made it quite clear

That He has a place for every Bombardier,

And for all the boys - wherever they fight

For the love of our freedom and all that is right.

So mothers and fathers, if that telegram comes,

Remember that God will take care of our sons.

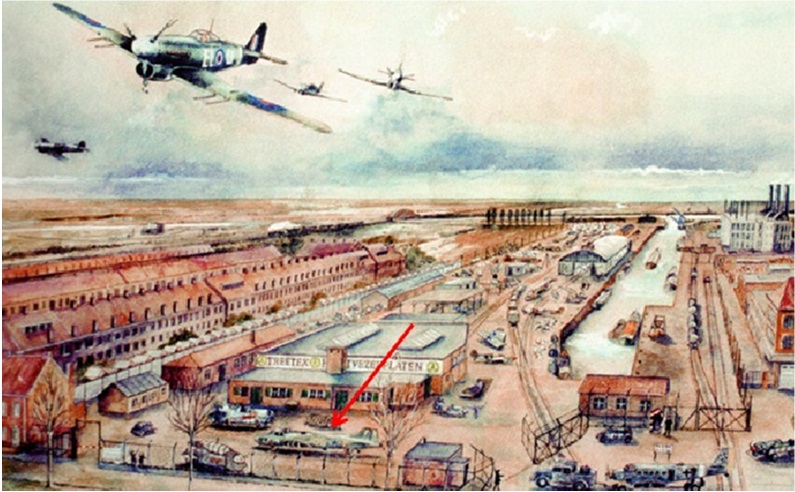

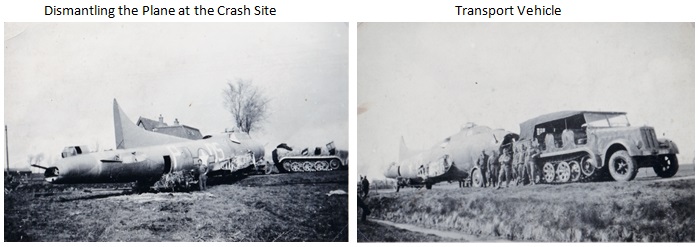

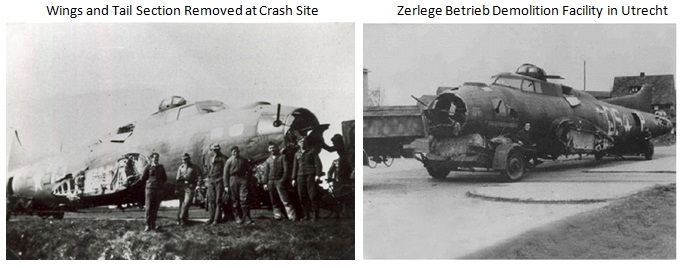

Meanwhile, the "No Balls", which had served her crews and our nation's war effort so well with her twenty-four completed missions, was being unceremoniously disassembled by the Germans to be used as scrap for their own war effort against us.

Photos acquired post-war by Mr. Jan van der Beek and provided

for this website courtesy of Mrs. Janny Herfst

Hoofddorp, The Netherlands

Courtesy of the CRASH Air War and Resistance Museum '40-'45

Aalsmeerderbrug, The Netherlands